On The Other Hand . . .

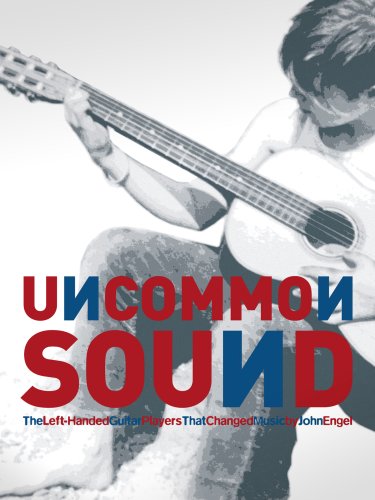

Uncommon Sound

The Left-Handed Guitar Players That Changed Music by John Engel Copyright © 2006 by Left Field Ventures sprl

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied, retrieved or stored in any form whatsoever or by any means now known or hereafter invented without prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief passages quoted within articles or reviews where the source is clearly indicated.

The text of the Olle Halsall chapter us reproduced here with permission.

![]() FLIPBOOK (Best for desktop/laptop)

FLIPBOOK (Best for desktop/laptop)

![]() PDF (Best for mobile)

PDF (Best for mobile)

TEXT ONLY BELOW

Peter ‘Ollie’ Halsall contributed one of the most diverse and intriguing bodies of guitar work in the pop/rock field, yet he is relatively unknown to the public at large. Many established guitar players, in awe of his phenomenal technique and inventiveness, came to listen to his performances with Timebox in the late 1960s and then Patto in the early 1970s. Damned with the praise of being a “guitarist’s guitarist” or “musician’s musician” in his heyday, Peter Halsall was the epitome of rock guitar’s anti-hero.

Ollie Halsall grew up in Southport, a small seaside town just north of Liverpool, home of his favorite pop band. His innate talent for music was all-encompassing. No other passion ever seized his interest. His father played the euphonium in a local brass band and introduced him to records of guitarist Bert Weedon, whom young Halsall would watch on television in the mid-1950s. Then, before succumbing to Beatlemania, Halsall’s two older sisters initiated him into rock’n’roll, mainly Gene Vincent and Johnny Ray.

Friends turned him on to Django Reinhardt, who was a major influence in his early years, enlightening him, as he once put it, “to certain attitudes of guitar playing, i.e., to develop the instrument.” He tinkered with a guitar at age seven, but his first serious instrument was the drums. Later on, he would also learn to play piano, vibes and bass with equal proficiency.

Halsall played drums in a variety of local skiffle groups, starting with Pete and the Pawnees and then the Gunslingers, together with schoolmate bassist Clive Griffiths. At 13, Halsall joined another mate, keyboardist Chris Holmes, in The Music Students, which had real paying dates. And then it was on to Rhythm and Blues Incorporated in 1964. Around that time his nickname solidified, deriving from a shortened form of his last name: ‘Alsall, Aly, Olly, Ollie.

By 1965, after graduating from Southport Art College at 16, Halsall went pro and headed down to London at the invitation of Griffiths who wanted Halsall and Chris Holmes to join him in his band called Take Five. However, as Geoff Dean already occupied the drum stool, Halsall was enlisted instead as a vibes player! They played originals and jazz covers, and mixed jazz with pop in a style that Halsall described as “neo-quasi jazz.” “Griff, the bass player, asked me to play vibes, which I’d never played before. I practiced on strips of paper until I got vibes, then I listened to Milt Jackson records and copied solos. I always wanted to be a vibes player… Griff knew this and he sensed I was a natural musician because I was a pretty good drummer.” (1) In fact, Halsall’s parents agreed to buy him a vibraphone on condition that he would first learn how to play one. He not only honored the deal in short order but he quickly went on to display amazing prowess and maturity on the instrument. John Halsey, a veteran session drummer and alumnus of Timebox, Patto and the Rutles, was a close friend and collaborator of Halsall’s:

JOHN HALSEY: “He bought some vibraphone mallets, cut out strips of paper and hit them with the four mallets, with the piano behind him so he could suss out what the notes were. And then after a while he told his parents he could play and they took him down to NEMS, Brian Epstein’s old shop in Liverpool. They wheeled out a vibraphone and he played it!”

CHRIS HOLMES: “Ollie’s parents bought him a set of vibes and we came down to London in the autumn of 1965. We were a basic pop-covers band, but Ollie was playing vibes. On the novelty of that, we got our first job. It was a residency in a comedy/night club called the Whisky-A-Go-Go. It is where Georgie Fame, the Pink Flamingos, and all these soul people used to play.”

“The vibes sound good mixed with another instrument. Vibes and electric piano is a really nice mixture... And, of course, they are a really interesting instrument for soloing on... Milt Jackson and Buddy Hutchinson show off the different attitudes to vibes playing that people have. You can either treat them like a percussion instrument or like a keyboard. Hutchinson really bashes them, he plays really percussively, whereas Jackson is a much more broad player, he plays in a very pure way... Personally, I like to treat the vibes as a percussion instrument – it’s more like playing a drum kit than a piano, for example.” (2) Besides Halsall, Griffiths, and Chris Holmes (on dual Hohner Symphonic 30’s), Take Five included Kevan Foggerty on guitar and Peter Liggett on vocals, later replaced by Frank Dixon, and then again by a U.S. Army deserter named Richard Henry. Within a year they had changed the group’s name to Timebox. Their well-rehearsed performances and highly unconventional combination of instruments and musical styles turned them into one of London’s top bands. They played the city’s trendiest clubs (Anabelle’s, the Speakeasy, the Whisky-A-Go-Go, etc.) and most prestigious dates and parties.

CHRIS HOLMES: “We were basically starved, the usual rock’n’roll story. We did a number of trendy club gigs in London, trendy discotheques where people like the Animals and Chris Farlow were posing about. Places like the Scotch of St.James, full of beautiful people, debutantes, rich young things... It was all quite different for us from our provincial town in the North of England.”

“The novelty at the time was the vibraphone. It was quite accepted, of course, in jazz circles. It was a bit pretentious in a way because we were doing more pop material. We did covers of Ben E. King, the Lovin’ Spoonful, and rarer, lesser-known songs.” Intrigued by the inclusion of vibes in their lineup, Laurie Jay, a drummer-turned-agent for the George Cooper Agency, took the band under his wing and sent them touring with the Kinks, the Small Faces, Tommy Quickly, and others.

JOHN HALSEY: “The group had two managers, the two ‘Lauries’: Laurie Jay and Laurie Boost. Jay was on the music side of it and Boost was on the money side. They were putting bands in American air force bases because there were loads of them and they used to have bands seven nights a week. And there was the officers’ club and the other ranks’ club. You had to work about four hours a night with three ten-minute breaks. It was absolute murder. Laurie Boost would collect the money from the gigs and we were on a flat wage of £15 a week. It wasn’t much even then. We worked all the time – in American bases, in clubs, at parties, nonstop. We would go for months without a single night off.” In early 1966, Laurie Jay booked Timebox on a 14-week season gig at Butlin’s Holiday Centre in Yorkshire, where Halsall decided to spend his leisure time learning to play guitar. He borrowed Kevan Foggerty’s guitar and spent hours a day practicing. On stage, he kept his post as vibist, but would wander off and take over Foggerty’s guitar from time to time. Deep down, he once said, he had always been a guitarist.

CHRIS HOLMES: “He just took Kevan’s guitar, turned it upside down, and played ‘Green Onions,’ much to the disgust of Kevan! He didn’t own one, but I’m sure he had picked up some guitar chords before. He played Kevan’s guitar the only way he could play it: left-handed upside down. Quite a few months after Butlin’s, he went and bought a guitar [and converted it to proper left-handed stringing]. He did practice very, very rigorously.” JOHN HALSEY: “I’ve seen him pick up Bernie Holland’s guitar, or anybody else’s guitar, all strung upside down, and it didn’t seem to make any difference to him. He just seemed to think, ‘Oh, it’s up the other way.’ And he natural to him. He just played exactly the same. He was ambidextrous with his mind. Overnight, Ollie became this MONSTER. Virtuosity beyond belief. He played piano as well, with two fingers. Just one finger on each hand. But so well that he would blow people like Tim Hinkley away.”

Timebox was signed to Piccadilly Records and, in February 1967, they released their first single, “I’ll Always Love You.” Halsall stepped in as, in his own words, “a 17-year-old vibraphone-playing singing twit.” Their second single was made up of two unremarkable instrumentals penned by Halsall, “Soul Sauce” and “I Wish I Could Jerk Like My Uncle Cyril.” In the spring, Jay hired John Halsey, of Felder’s Orioles, to take over on drums.

JOHN HALSEY: “Ollie and I would often share bedrooms to save money. He would be sitting twiddling away on his guitar, driving me bloody mad (I was trying to get some sleep). We went off on holiday one time – our manager gave us all money. And Ollie and I and both of our wives went away to the East Coast of England. He took his guitar on holiday and he would just sit and play his guitar all the time – scales and scales and scales and practicing.” On a night of June 1967, Michael Thomas McCarthy, aka Mike Patto (19421979), happened to jam with Halsall at the Playboy Club. A singer at ease in jazz as well as pop and a man of unusual comedic talents, Patto had kicked off his solo career with a 1966 single for Columbia Records. Halsall invited him to join Timebox as lead singer. But, before the lineup set off on another tour of U.S. Air Force bases in July 1967, Foggerty left the band and Halsall began his official career as a guitar player. He had come full circle to his original calling.

Thus, Halsall learned to play yet another instrument in record time. For years to come he would continue to double on vibes, which partly explains the distinctive fingering technique he adopted. Indeed, in order to switch quickly between vibes and guitar, he kept his guitar strapped high around his neck. As a result, his thumb was confined to the back of the guitar neck and he fretted the strings with all four fingers in a manner more consistent with classical guitar playing. By using all four fingers he was able to develop unprecedented speed, which he further enhanced by perfecting a hammerhammeron technique, whereby he would only strike a string with his plectrum every two, three or four notes, while the intervening notes sounded off by hammering them on the fret board with the fingers of his right hand. Thus, his solo runs could flow with lightning speed and transparent fluidity.

Barry Monks, archivist of Halsall’s career, puts it in pragmatic terms: “Halsall could play very fast and was the first to discover how to do it. Second, and more importantly, he possessed a melodic sense that transcends any formal analysis.

The quintessential example of this would be in his unique guitar/vocal ‘duets.’ He incorporated minor 11th and 13th jazz patterns and – this is the point – he didn’t sing along with the guitar, he played along with the singing! He could play anything he could sing and, when you think about it, that is just about the ultimate form of musical expression.” The late session guitarist Martin Jenner (see earlier in this section) said, “Ollie was a great player. He was one of the major guitar heroes of the times.

He started all the legato stuff, even before [Allan] Holdsworth.” Though the legato four-finger hammer-on technique has long become standard fare, championed by famed players like Edward Van Halen, Joe Satriani, Steve Vai, Eric Johnson et al, it should be noted that Ollie Halsall had it down in 1967 and may have been the first guitarist ever to develop it to that particular extent. Whether or not he was seen and emulated by others is impossible to say,

although many top-flight musicians came especially to see him play in the late 1960s and early 1970s, including Boz Burrell (Bad Company, King Crimson) and Bernie Holland, to name a couple.

JOHN HALSEY: “When we were on tour with Ten Years After, they let us use their p.a. Alvin Lee had a Revox recorder connected up to the mixing desk so he could record gigs. Alvin was absolutely flabbergasted by Ollie. Had never heard of him before. He started to hang with him and traveled in the group van with us instead of his limousine. They were big stars at the time. It was quite a big tour, big audiences. We were the openers of the show. But we might as well not even have gone on. The audiences ignored us. It was depressing!”

On August 12, 1967, their performance at the Windsor Jazz Festival caught the attention of Decca Records producer Gus Dudgeon (later to become famous as Elton John’s producer), who signed them to Decca’s new subsidiary label Deram. True to the wisdom and vision reserved to office executives, Deram’s powers-that-be decided it was best to market Timebox as a pop group in line with the then-popular Marmalade and The Herd. Their first single came out in October 1967, to be followed over the ensuing two years by a string of chart-hopeful singles, all of them incongruous with the true spirit and sound of the band. Only “Beggin’,” a cover of the Four Seasons song, actually achieved chart status at number 38 in the spring of 1968.

Timebox enjoyed the acclaim of the press and musicians alike; they had a solid following in the hip London scene. However, provincial audiences expected Timebox to reproduce the sound and style of the massively orchestrated singles they put out – which the jazz-tinged fivesome were not able, let alone keen, to deliver.

The early 1968 recording sessions also yielded the first Patto/Halsall writing collaborations, vaguely conceived for an album to be titled Moose on the Loose. Mike Patto enabled the group to further their unique blend of jazz, soul, blues, and pop. Their concerts may well have presented audiences with the very first expression of a jazz-rock idiom, or fusion, both terms that had yet to be coined. The tight rhythm section of Halsey and Griffiths was able to follow Halsall’s every change of heart on a dime. The melodic mix of Holmes’ organ, Halsall’s vibes and guitar and Patto’s voice gave them a truly unique sound. Although no such recordings appear to have survived, Timebox played on several radio and television shows of the day.

“Yellow Van,” Timebox’s last single, an original composition, was released in October 1969. The sexual overtones of the lyrics were judged offensive enough for the song to be banned from the radio. Nevertheless, the controversy did not manage to spark an increase of sales or an entry in the charts.Material for two albums had been recorded, the aforementioned 1967 studio numbers for Moose on the Loose and a pretend-live set recorded at ‘Club Noriek,’ Tottenham, London (in fact a bingo hall where the band rehearsed), but neither of them was ever officially released. Currently, The Deram Anthology (1998, Deram) is Timebox’s only available CD, and an excellent illustration of Halsall’s early guitar work.

In 1969, echoing the pundits’ general appreciation for Timebox, Melody Maker’s Chris Welch promised fame and fortune for the group, but neither status was to be achieved. In 1970, Mike Patto, Ollie Halsall, John Halsey, and Clive Griffiths forged on and signed with Vertigo Records. They hooked up with producer ‘Muff’ Winwood, ex-Spencer Davis bassist, and set out to record the kind of original material that had brought them considerable local success. At the time, group names listing the last names of their members were in vogue but these fellows’ names were found too difficult to pronounce in markets outside of England. So they opted for Mike’s stage name: Patto. Belying its name, the group functioned quite democratically, but much of the attention was focused on Halsall’s own virtuosity.

Their first album, the eponymous Patto, was released in late 1970, a mix of heavy rock and jazz, the bulk of which was co-written by Patto and Halsall. Highlights include “Hold Me Back,” “Money Bag,” and “Red Glow,” all of them showcases of Halsall’s innovative musical style. Their second album, Hold Your Fire, came out in late 1971 and features some of Halsall’s best guitar work ever recorded.

MIKE PATTO:“Take Ollie’s tunes. He doesn’t fill them with fashionable rip-offs from other people’s material, neither are his guitar solos in the current fashionable trend. Ollie is an individual, and I feel that a great deal of our success hasn’t been because of my visual antics out front but because of Ollie’s great songs.” (3) JOHN HALSEY: “The music did not grab people’s imagination. Clive and I, although being recently proficient players, were not Lake and Palmer. But Ollie’s guitar playing was incredible.”

Attending a Patto gig was an unusual experience. The ambience was that of a chaotic party. The music was a heavy brand of rock inflected with jazz tones and chord progressions. The songs followed no set list, as Halsall simply played the intros and the others followed suit. The performances were infused with Python-esque humor throughout, led by arch-loon Mr.Patto himself.

Typical ‘party pieces’ included the a cappella “Dwarfs’ Chorus” (“Hi-ho, hiho”), approximated visually by the group members kneeling on their shoes; the rendition of “Strangers in the Night” in 5/4 time achieved by adding an expletive before the last word in each phrase; or a twist competition among band members to the tune of “Walk Don’t Run,” wherein Halsall did his ‘amoeba twist’ routine: he lay prostrate on the floor and wriggled his body sideways. Halsall had once come up with this bit when needing to loosen up an unfriendly gathering of skinheads.

During the Patto days, Halsall continued to play both guitar and vibes but, after smashing his vibes to pieces in late 1972 (due to an excessive Keith Moon impression), he replaced the latter by appropriating Mike Patto’s electric piano. The group established residency at the Marquee, drawing countless peers to marvel at their odd mix of buffoonery and musicianship.

JOHN HALSEY: “We were used to playing the clubs. We would play really well, and then muck about and do some silly songs, and then play a bit more jazzy stuff, and then do another couple of silly bits, and then some rock’n’roll. That’s the way we carried on.”

While they were ideal within a club setting, the group’s antics did not work in a large concert hall, let alone a football stadium. There was something urgent and personal to the whole event that could not transfer to the faceless realm of major concert venues. For their tour with Joe Cocker in the U.S. and Australia, the group followed their management’s advice to cut the humor. Patto sang, the others played; the result knocked out musicians and cognoscenti, but left the general public indifferent.

JOHN HALSEY: “I think we got better at playing big audiences. We did two tours with Ten Years After and one tour of Germany with Rod Stewart. We started doing other things on stage, and then we did the huge U.S. tour with Joe Cocker, playing these massive auditoriums, 20,000 to 30,000 seats. By the time we were playing our last gig at the Hollywood Bowl we had learned what to do to get the audience going. By the end of our three numbers we brought the house down. They were standing on their seats.“Patto definitely has a place in British rock history. The band was never very successful, but it was slightly important and definitely influential. You need to be in a band that is good for the proletariat. When you’re playing for musicians in London, you’re playing for 400 people – the ones who aren’t working. If you’re playing for the proletariat, like Queen did, you’re playing to 400,000 people!” Halsall’s musicianship received accolades from his peers and fans. His technique seemed to be years ahead of its time and his playing style resembled no one else’s. Halsall claimed he hardly ever listened to other guitar players.

He acknowledged having been impressed by The Beatles and a diverse range of guitar players such as Scotty Moore, Buddy Holly, Charlie Byrd, and Arthur ‘Guitar Boogie’ Smith. But the only guitarist he actually listened to through the years was Django Reinhardt. Other than that, he preferred listening to other instrumentalists and different musical styles, from music hall to bebop. He used to like Stockhausen, Charles Mingus and Eric Dolphy and was especially enamored with piano and saxophone, trying to apply their structures and attacks to his own approach. He would emulate sax phrasing by timing and modulating his guitar-solo runs to his own breathing. Pianist Cecil Taylor and sax players Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane were among his favorites.

Halsall’s introduction of bebop jazz phrasings in a rock context was novel. So were his multi-octave excursions and fluid leads, emulating the saxophone flurries of Coltrane or Charlie Parker, where the plectrum does not hit every note, leaving the fretting hand to perform distinct hammer-ons and pull-offs to produce lightning-fast note progressions. With vast musical imagination, Halsall used every facet of the electric guitar, whether the inherent sustain or the vibrato arm or the 22 frets. However, he believed in using a fairly clean tone and avoided the use of feedback or heavy distortion.

His demeanor on stage fit the bill of an anti-hero – unintentional by definition.He often stood in the shadow, to the side behind the vibraphone, fully absorbed in the music, wearing some unfashionable outfit. He was indeed a paradox and, to make his accomplishments more mystifying, he was left-handed.

“I would like to play guitar the way [Cecil Taylor] plays piano – which is totally devoid of any tonality or any rhythmical structure at all. We went through that stage with Patto. “I deplore guitarists who just sit down and copy a solo they’ve heard and then make a few alterations. A lot of people copy things. You see, if I bought a Jimi Hendrix record, that would be it. It would destroy me. I’ve heard his records, but if I sat at home with one and lived with it... I know what I’m like. I get influenced terribly easily… To be honest, I’m more into people and situations than the intrinsic technicalities of music.

“Don’t go to Top Gear or Orange for your guitars, don’t listen to any music, don’t buy any records. That [you are supposed to listen to other people’s music] is bullshit. Do that and you’re perpetuating the whole trip – just another suburban Clapton.”

JOHN HALSEY: “The fact that Ollie didn’t listen to anybody was true, but I think it was mainly because he couldn’t afford to buy any records. None of us could. If anybody made him listen to something, he would listen to it and be fascinated by it. We’ve done gigs with bands like Free. The next time we all turned up to rehearse some new songs, he would have a song that would sound just like a Free song.”

To what other factors should one attribute Halsall’s exceptionally individual technique and melodic approach? In a typically self-deprecating bent Halsall points out that the freshness of his playing is also to do with staying off the touring grind and star status:

“[My guitar playing] has always been completely spontaneous because I’m basically bone-idle. The only world tour I ever went on was as support with Patto for Joe Cocker. Even then I really had to fight not to end up playing the same notes every night. People expect you to play the same over and over. It’s like having to play your greatest hits. Not that there’s a lot that can be done anymore. It’s down to the individual. I’ve got the same guitar as everyone else, the same strings.

“So many guitarists are into following people, they’re searching for something. But I’ve already found it – I know that sounds arrogant. What I mean is that I know what I’m doing and I know that because of the way I approach it, to a certain extent probably about sixty per cent of what I play comes out sounding new.”(5) As for playing at home, Halsall favored acoustic flat tops. One of his practicing tricks resembled that of a basket ball player who trains in weighted shoes in order to jump higher during the game: he trained with heavy-gauge strings and a high action, so that, once on stage, the light strings and low action on his electric guitar enabled his fingers to fly across the fretboard.

“I use an old acoustic of mine for composing on. It’s a scaled down classical guitar – it has a regular sized neck and a small body. It’s a little bit like a six-string ukulele. Usually when Mike Patto and I write together, I’ll come up with a chord sequence first and he writes the words afterwards. I get ideas for music when I’m walking about or on trains or buses and then I transpose those ideas onto the guitar.”(6) “[In the recording studio] we just go in there, set up the mics and play. We try to do as much of it live as we can, but when I have to play guitar and piano on the same track we can’t... [On stage] I’m playing just a bit of piano, mostly guitar, as Mike is handling the keyboards...I’m handling the leaping about and the guitar.”

In the course of 1972, Halsall undertook or collaborated on several side projects, including recording sessions and two solo albums – one under the pseudonym of Rusty Strings and one under the name of Ollie and the Blue Trafs. ‘Traf’ spells ‘fart’ backwards and, well, “the record is music to traf to,” said Halsall. The album was produced by none other than Robert Fripp and recorded in January at London’s Command Studios with Halsall on piano, and the help of musician friends from the circles of King Crimson, Patto, and Centipede.

JOHN HALSEY: “Playing on ‘Ollie and the Blue Trafs’ was a really good moment. It is more avantgarde jazzy than rock’n’roll. I don’t think there is a copy of the album in existence. It is a shame it disappeared – although the masters may still be sitting in Bob Fripp’s vault.

“For the Rusty Strings project, Muff Winwood said to him, ‘Why don’t you come into the studio and do really straight-ahead stuff like The Shadows and call yourself a different name.’ So he went into the studio, called himself Rusty Strings, and recorded this bloody awful album of lift-music. That was another attempt to make money.”

In May 1973, feeling that they could no longer break new ground, Ollie Halsall left Patto.

JOHN HALSEY: “It was weird what was happening during the recording of the last album [Monkey’s Bum, recorded in 1973 and unreleased until it was unearthed by Audio Archives in 1995]. Anything that Mike Patto had written Ollie wasn’t playing well at all. He would play one-string solos, sabotaging the songs. After a couple of days, Mike (who was quick-tempered) flared up and Ollie said, ‘I’m just not enjoying it anymore, I don’t want to do this anymore.’ He packed up his guitar, walked out of the studio, and that was the end of the band. We finished the album, putting on some horn players and stuff like that, presented it to Island Records, and they said, ‘No. Without Ollie, we’re not interested.’ After the Patto days, Ollie was always a great player, but he never again played like he played with Patto.” Days before quitting Patto, Halsall was invited by drummer John Hiseman to join Tempest and, on the following day, played a 55-minute live show with them on the BBC together with guitarist Allan Holdsworth. There seemed to be some friction, or competition, between the two guitar players and Holdsworth left the band soon thereafter, as did the singer (Paul Williams). The band was down to a trio made up of Halsall on guitar, lead vocals and keyboards, Hiseman on drums, and Mark Clarke on bass, vocals and piano. They toured around the UK and recorded an excellent album entitled Living In Fear (1974, Bronze) at AIR studios in London.

Halsall wrote, or co-wrote, about half of the heavy rock songs on Living In Fear. While his guitar work is jaw-dropping, he also experimented with synthesizers on the record as well as in live shows, which would be the first and last time he did so. He later dismissed synthesizers as awful instruments, much preferring acoustic instruments or the electric guitar with a minimum of effects. The added harmonics of distortion and other effects were superfluous to the clarity and precision of his technique. “I play very organically. I like to think there’s nothing between the guitar and the amp to distort its natural sound... I don’t really like instruments that are too electrical... You can get some great effects using the [vibrato] arm... That’s what I like about the guitar, it can sound like so many different things.” (April 1976, Beat Instrumental, ‘Player of the Month,’ by Peter Dowling)

The recording session for Living In Fear opened the door for the collaboration that would become Halsall’s longest and most consistent of his postPatto days. Kevin Ayers was recording his Confessions of Dr. Dream and Other Stories (1974, Island) next door to Tempest. One day, he asked Halsall if he would play a solo on a song of his. Ollie obliged and put down a blistering solo on “Didn’t Feel Lonely Till I Thought of You.” They had known each other since the Patto days, and Kevin Ayers had played on the same bill at the Roundhouse theatre in London in early 1972.

KEVIN AYERS: “He was with John Hiseman’s Tempest at the time. I saw him walking down the corridor carrying his guitar and I said, ‘Hey, fancy doing a solo on my album?’ He said sure. He came in, listened to it twice, and played an absolutely stunning solo. And it was love at first sight really.”

“I was always more interested in singing and songs, and writing, than instrumental things. But John Hiseman always wanted an instrumental-based band. I’m an instrumentalist, I can cope with that. But I always thought that John was using me as his passport to some sort of commercial utopia that he’d never reached, and he thought he was going to reach it through me.” (8) A few months later, just as Halsall was wearying of Tempest’s restrictive style, Ayers invited him to tour with his band, the Soporifics. They toured around the country and finished at the Rainbow in London for an ACNE (Ayers-Cale-Nico-Eno) concert with Brian Eno, John Cale, and Nico that was recorded and released as the LP June 1, 1974, an experience that Halsall found fruitful and enjoyable.

In mid-1975, a few successful Patto reunion concerts motivated Halsall and Patto to resume their writing partnership. They formed Boxer, a straight ahead four-piece rock band.

JOHN HALSEY: “Eric [Swain], who had been our roadie for years, got murdered in Pakistan. We got together again to do some gigs to raise money for his wife and kids. The gigs were absolutely amazing. Hundreds and hundreds of people turned up to these tiny little gigs. The Torrington only holds about300 people if you squeeze, and there were hundreds of people who couldn’t get in. I recorded the Sheffield show and released it as a live album entitled Warts and All [1999, Admiral]. Ollie’s guitar playing on it is just the most incredible guitar playing I have ever heard. Those gigs were really where Boxer started. Mike and Ollie had fallen out and didn’t speak to each other for years and then, after these gigs, Mike put together Boxer with Ollie and Tony Newman.”

Halsall recorded two LP’s with Boxer in 1976, Below the Belt and Bloodletting (release of the latter was postponed to 1979). While Below the Belt keeps it trucking in unabashed rock form, mixing in the odd funk and blues references, the melodic and chordal context is full of inspired twists and turns worthy of Halsall and Patto who penned most of the tracks, separately or together. Bloodletting is made up of covers and a few good Patto compositions, but that album lacks the joyful creative spin of the former release.

Once again, the artists’ attempt to reach the big time failed. By late 1976, Halsall was off. Diagnosed with lymphatic leukemia in mid-1976, Mike Patto went on to record a third and final album with Boxer in 1978 entitled Absolutely. He died on March 4, 1979.

While working with Boxer, Halsall lost all his instruments and gear due to the band’s serious financial straits. Yet he still managed to borrow instruments and play on a wide variety of projects in the following years. By the early 1970s, he had begun to work as a session guitarist on other artists’ recordings and would continue to do so steadily until 1976, when he declared: “I won’t do sessions anymore. It’s like being a plumber. They get you in to patch up a track.” He recorded with many artists, including continued work with Kevin Ayers, and contributed all the guitar parts to Andrew Lloyd Weber’s 1973 album Jesus Christ Superstar.

JOHN HALSEY: “Playing-wise I’d say Ollie’s best guitar contributions were in the Patto days. But, once he started doing sessions for people who weren’t with Patto, he learned to play very sympathetically and he was really good at doing that. Whoever he played with, Ollie was always just what they wanted. He could provide what people needed, he didn’t have just one style.” Out of necessity, Halsall reluctantly resumed session work in late 1978. Around that time, he even did a stint as the lead guitarist for Gary Glitter’s Glitter Band, and reached the first of several low points in his life.

JOHN HALSEY: “I think he liked Gary Glitter and he liked the madness of Gary Glitter. Glitter called him in his dressing room one night and told him, ‘I want you to run around in small circles and blaspheme.’ ‘Why is that?’ said Ollie. ‘Because my mom said if you do that, it will be a good gig tonight.’ Gary’s mom was dead at the time. But Ollie went, ‘Okay.’ He went around in circles, going [long string of curse words] and then stopped and went, ‘Is that enough?’ Then Gary looked up to the ceiling as if his mom was stuck up there and said, ‘Is that enough mom?’ And then he looked down at Ollie and said, ‘No, a little bit more.’ So Ollie did a bit more and that was enough. That craziness appealed to Ollie.

“But I don’t know how he got so low. He probably never earned enough money to make ends meet. He could be a very difficult person. His wife Monica and their two daughters left him. He picked up with this woman friend of Julie Driscoll’s who was in the National Front. Somebody saw him down Oxford Street handing out neo-nazi leaflets. Really strange. He read Mein Kampf a couple of times. He never used to be like that. He became a gang of one. One night he told Glitter’s managers what he thought of them (I don’t know what), and they followed him into the toilets and beat him up. He ended up in hospital. He never worked with Gary Glitter again.”

Despite his living in near-total poverty during much of that time, the period from 1976 to 1981 brought Halsall several projects and a couple of memorable engagements. The first was Neil Innes’s invitation in 1977 to play in The Rutles, the parody of The Beatles starring him and Monty Python comedian Eric Idle. Halsall played guitar and keyboards on all the songs for The Rutles (All You Need Is Cash) (1978, Rutle Corp.), and recorded vocal parts for the made-for-TV movie, in which he did not appear. (Incidentally, Eric Idle pretended to be left-handed for his McCartney-like role.) Archaeology (Virgin), a second album by The Rutles, was put out in 1996 featuring some tracks with Halsall from the original 1977 sessions.

JOHN HALSEY: “When it came time to shoot the film, the production company in America said, ‘The only thing we can really sell this on is Eric Idle’s name [because of the Monty Python association].’ So they wanted Ericto play the McCartney character as well as the interviewer/narrator, and Ollie got written out.”

Halsall’s other important project in the late 1970s was the recording of personal song demos, on which he played all the instruments, including saxophone, and sang all the vocal parts. The home recordings became a CD entitled Caves (Market Square), released posthumously in 1999 thanks to John Otway with whom Halsall had collaborated in the late 1970s. The songs are crafted in a typical pop vein – a far cry from the jazzy explorations of the Patto days or the hard-hitting rock of Tempest.

Whether Halsall did less session work by design, as he had stated in 1976, or as a result of his isolated living situation is hard to tell. Thankfully, his friend John Halsey involved him in a number of recording projects in 1980 and 1981.

JOHN HALSEY: “He lived 30 miles outside central London. He couldn’t drive a car. Once he had his phone cut off, nobody knew where he was. I got together with him round about 1980 to do jingles for television and radio and we did some work for Kevin Ayers. We were rehearsing out at his house with no electricity. We did the Tiswas album with Clive Griffiths and other people. Ollie and I wrote songs together to showcase his guitar playing. We recorded demos and tried to put a band together. We wanted a bass player who could sing, but it never worked out.

“I was also doing a lot of work with Viv Stanshall and got Ollie involved with that. Viv was over the moon – he couldn’t believe this guy. When we got paid for Viv’s album, we got about £600 each. Ollie went out and bought a set of blueprints to build an ocean-going yacht. He stuck them all around his walls. I went around to see him one day when we were writing these songs. I asked him, ‘Did you get your money?’ He said, ‘Yeah, come and see what I bought.’ ‘What are they?’ He said, ‘They’re plans. I’m gonna build a yacht and sail around the world.’ I said, ‘Why didn’t you buy a guitar?!’ He wasn’t insane, he just didn’t have any sense. He didn’t dare answer the door because he hadn’t paid the mortgage or the council tax. By that time, he was living in this house with a fourteen-yea-rold girl named Susan. In 1980, Ollie was about 31. Sometimes they were going out stealing food to survive. And when he got £600, he spent it all on drawings to build a boat!

“We did those projects, and then Ollie disappeared. Bill Lovelady, an old school friend of Ollie’s, had a hit record in Sweden. He asked Ollie to do this tour with him there. So Ollie left his house and his girlfriend, said he’d be back in a couple of weeks, and that was it. He met a Brazilian girl out in Sweden [Zanna Gregmar] and then moved off to Spain.”

In 1981, after the Swedish tour with Bill Lovelady, Halsall went down to Spain and took up residence in Deia, a village on the northwest coast of the Balearic island of Majorca, where Kevin Ayers lived.

KEVIN AYERS: “Ollie recontacted me actually. He sent me a telegram saying, ‘I love you. Let’s work.’ Can’t resist that!”

For the remaining ten years of his life, Halsall would divide his attentions between recording and touring with Ayers and a spate of rock projects with over a dozen Spanish bands for whom he contributed guitar or keyboard parts and produced dozens of singles and albums.

Kevin Ayers and Ollie Halsall were very compatible souls: Ayers brewed quirky musical ideas and wrote lazily provocative lyrics; he disdained the trappings of fame and embraced life as an eccentric bohemian artist. At his best, he took the ‘pop song’ on exotic rides, crafted within pop parameters, yet happily off the mainstream. With Halsall’s participation, Ayers distilled sophisticated compositions, originally produced but not self-indulgent.

Often, Halsall’s brisk and intricate guitar work provided an interesting counterpoint to Ayers’ low, charismatic voice. Several Kevin Ayers recordings stand out as showcases of Halsall’s musical eclecticism and sensitivity. Sweet Deceiver (1975, Island), one of Ayers’ most cohesive albums, contains exquisite guitar work by Halsall. Yes We Have No Mañanas (1976, ABC) includes stellar turns on lead guitar as well: “Star,” “Blue,” “Help Me,” and “Mr. Cool” are but four quintessential examples of Halsall’s guitar style: surprising, humorous and intricate, head-turning one moment and strangely moving the next.

KEVIN AYERS: “Ollie is the most underrated guitarist in the world. He could play so well slowly as well as fast. You don’t often get the two together. Even though he could play a hundred miles an hour, he didn’t do that if it didn’t fit the song or the composition. He didn’t use his speed just because he could. I love the very short, slow solo he played on ‘Blue.’ It’s magical.”

During the Spanish period, several Ayers albums belie the depth of Halsall’s contribution, owing to the restraint of his performance. Falling Up contains some inspired turns, such as the succinct solo on the moving ballad “Another Rolling Stone,” but most of Halsall’s input is meshed within the production. On the other hand, As Close As You Think (1986, Illuminated) makes up their most symbiotic partnership on record. The label of ‘Kevin Ayers Featuring Ollie Halsall,’ under which it was released, could almost be reversed. Halsall arranged and produced the record, played a variety of instruments, and wrote or co-wrote most of the songs. His guitar is a prominent participant and he even sings lead vocals on one track. The album’s opener, and perhaps the best cut on the record, is his own “Stepping Out,” which is one of the songs found on Halsall’s Caves demo. Nevertheless, the album as a whole sadly lacks the inspiration that heightened, and tightened, the quirky creations on other Ayers records.

KEVIN AYERS: “We were a really good co-writing unit. Ollie never dealt with the lyrics, but he added so much in color to the music. I would write the words and the tune, then he would fill in all those bits that were far too clever for me to play, and he’d put it all together. He would arrange around what I was doing, which is all you need really: to be that sympathetic and good as well. He was brilliant to work with because he could play any tune and make it sound good. He was also a very good friend. We had so many things in common. He liked my work and I liked the way he could arrange it.” Other ventures in the 1980s included concerts and a live album with John Cale in 1985 and a week of concerts at the Bloomsbury Theatre with Vivian Stanshall (and John Halsey on drums) in 1988. But, despite several attempts to quit drugs, Halsall was unable to stay off the self-destructive spiral that would eventually claim his life.

KEVIN AYERS: “We both went downhill... He made a lot of money, spent it, and disappeared into this shadow world of fading Madrid musicians, descending into his own kind of despair which he never came out of.”

JOHN HALSEY: “The last time I saw him was for the concerts with Viv Stanshall [in 1988]. Jack Bruce was playing bass. During rehearsals Ollie, Jack, and I went out for a pint. Jack Bruce was an ex-heroin user, and then it came out that Ollie was an ex-heroin user as well. He was saying he’d been strung out quite badly and his days of using heroin were over. Obviously at that time he was off of it. He decided to go back on it for some reason – or maybe it was just the company he kept.”

Barely a month after finishing a tour with Kevin Ayers at London’s Shaw Theatre, Ollie Halsall was found lying on the floor of a Madrid flat, dead from a drug-related heart attack, on May 29, 1992.

His enormous talent struck everyone who crossed his path. Yet, the inner turmoil of the man remains a mystery. His contribution to music, too, has remained unknown to the public at large, even if MOJO magazine called him in September 2001 “one of the greatest guitarists of all time.” CHRIS HOLMES: “Most people can barely play one instrument, let alone play a gamut of instruments. He could learn instruments so quickly, and bring the best out of them, using them with empathy. Even though I toured and played with him for nigh-on six years solid, he was still quite a mystery in many respects. He was quite a shy person, quite temperamental and moody. I got the brunt of that a few times. He was burgeoning new skills as a keyboard player himself, and if I didn’t get something right straight away, he would blow up.

“He had such an exceptional music talent, he was mad as a hatter. You had to be to be in Patto. That madness started with [Mike] Patto joining Timebox, basically. And then Ollie got madder and, ultimately, we all got a bit madder and madder. Some of it was induced by substances, obviously. Although the music was taken quite seriously, there was a humor which was marvelous. That was the wonderful thing about it: character and humor.”

JOHN HALSEY: “Ollie could play anything. He was a great guitar player, but he would have been a wonderful tenor sax player. He could play drums really well too, left-handed on a right-handed kit. He had a touch for anything. He was a great lyricist and he could sing. He was very eloquent in his way.” KEVIN AYERS: “It was nice to have someone I felt close to and who was so good musically. I could trust him completely: whenever Ollie did a solo, I never had to worry about what it’s going to be like, it was just good and it stood on its own. I could just stand back a few paces and feel proud. Apart from the set pieces, he would never play the same solo twice. He was really exciting, his musicianship and his creativity were exceptional. I was never bored with anything Ollie played, ever.”

As with most artists, one finds contradictions within Ollie Halsall’s approach to music and to his career. Often described as a keen and everready listener, Halsall expressed utter disinterest in other guitarists’ work. He fluctuated between embracing collaborations with different artists and walking away from situations where he did not have the desired control. He scorned mainstream pop and defended wild artistic exploration; yet, he produced bubblegum pop and dance music for about ten years. As a musician, he was sensitive and refined, yet in his life he sometimes displayed baffling moral choices. Was he happy or was he dejected? Artists who have known Halsall have differing views.

ZOOT MONEY: “He felt guilty about being so brilliant. I’ve seen him play with a string going out of tune, no time to retune, but somehow he’d bend into it and make it work. And that was on a cocktail of drugs I wouldn’t even walk the dog on.”

JOHN HALSEY: “Ollie just never joined the right band. He was always hoping to be successful. Near the end of his life, he certainly tried to do more commercial things, with the Caves demo and with the Spanish pop bands that he produced. Yes, he did do things on the periphery of music but, bloody hell, if a successful band had asked him to join, he would have jumped at it. Why else does anyone join groups and sit and practice for hours? You hope to get some sort of recognition. Ollie did not choose to be avant-garde and overlooked.”

KEVIN AYERS: “I think Ollie was depressed because he wasn’t making enough money. But he didn’t want to be a session musician. He didn’t want to join in that business. He only wanted to play with people he liked playing with, and that doesn’t always pay well.

He could have been a super session man, earning a fortune and running around in a Rolls Royce if he wanted to. But he didn’t want to, he had his standards. I don’t think he would have liked to be in a huge rock group, actually. He was happy with weirdos. He didn’t like anything that was formulaic and predictable.” Whatever portrait of the man one sketches,

Halsall’s musical inventiveness and imaginative use of the guitar are incomparable. Because his contribution does not rest on epochal collaborations or memorable compositions, he is not discussed in the same breath as artists like Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton or Jimmy Page. Instead, Ollie Halsall’s unique talent can only be appreciated in his diverse turns as a highly creative virtuoso.

Halsall’s style on guitar combined typical rocker attitudes with unexpected influences. His contributions in the late 1960s articulated the foundations of jazz-rock, later known as fusion. From the late 1960s to the early 1970s, his work was effusive and off the scale of trends, genres, and techniques of its day.

From the mid-1970s on, although he often had less input in the overall musical compositions, his guitar approach gained in maturity and soulfulness. While still crossing boundaries and injecting swing-era phrases in rock’n’roll, country licks in pop solos, or blistering octets over ballads, he exerted more restraint and a deeper commitment to the support of the composition.

Ollie Halsall always played with wit and verve. An inner vulnerability inhabits some of his more sensitive performances. But, by and large, his guitar music represents less the searing weight of projected emotion than the product of a fragmented soul coming together through the catharsis of music. That is why sublimation is the essence of Halsall’s musical expression. His nonconformist approach has led him to play like no one else before him. Yet, that very same distinction has put him in a unique place in rock music as one of its most significant ‘unsung’ guitarists.